Posts

Piriformis Syndrome Part II- Evaluation

/in Conditions/by Dr. Kevin RoseClinical Diagnosis

Piriformis syndrome occurs most frequently between ages 40-60 and is more common in women than men. Some reports suggest a 6:1 female-to-male ratio for piriformis syndrome; , possibly because of biomechanics associated with the wider quadriceps femoris muscle angle (ie, “Q angle”) in the pelvis of women. Reported incidence rates for piriformis syndrome among patients with low back pain vary widely, from 5% to 36%.

The most common symptom of patients with piriformis syndrome is increasing pain after sitting for longer than 15 to 20 minutes. Many patients complain of pain over the piriformis muscle (ie, in the buttocks), especially over the muscle’s attachments at the sacrum and medial greater trochanter. Symptoms, which may be of sudden or gradual onset, are usually associated with spasm of the piriformis muscle or compression of the sciatic nerve; these symptoms include radiating/shooting pain or tingling or numbness in the back of the thigh, leg, or foot. These symptoms must be evaluated by a healthcare provider to differentiate the possible causes. Patients may also complain of difficulty walking and of pain with internal rotation of the involved leg, such as occurs during cross-legged sitting or walking. X-rays or an MRI offer little help in directly diagnosing piriformis syndrome but may be used to rule out other causes of sciatica such as a herniated disc in the lumbar spine.

Functional Evaluation

There are many functional abnormalities that may have either caused or resulted from this condition. Once the diagnosis has been made, these underlying, perpetuating biomechanical factors must be addressed.

Functional biomechanical deficits associated with piriformis syndrome may include the following:

- Tight hip external rotators including pirifromis

- Tight adductors (groin)

- Hip abductor weakness

- Lower lumbar spine dysfunction

- Sacroiliac joint hypomobility

- Hyperpronation of the foot and prolonged toe-off

Functional adaptations to these deficits include the following:

- Ambulation with the thigh in external rotation

- Functional limb length shortening

- Shortened stride length

Next post will discuss treatment options for piriformis syndrome

Piriformis Syndrome: Overview and Causes

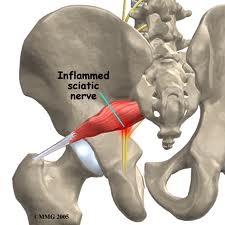

/in Conditions/by Dr. Kevin Rose Piriformis syndrome is a unique cause if sciatic nerve irritation (neuritis) or sciatica. The condition, which can mimic lumbar disc herniation, usually is caused by irritation of the sciatic nerve due to spasm and/or contracture of the piriformis muscle. Piriformis syndrome is also referred to as “pseudosciatica”, “wallet sciatica”, and “hip socket neuropathy”.

Piriformis syndrome is a unique cause if sciatic nerve irritation (neuritis) or sciatica. The condition, which can mimic lumbar disc herniation, usually is caused by irritation of the sciatic nerve due to spasm and/or contracture of the piriformis muscle. Piriformis syndrome is also referred to as “pseudosciatica”, “wallet sciatica”, and “hip socket neuropathy”.

It frequently goes unrecognized or is misdiagnosed in clinical settings. Piriformis syndrome can “masquerade” as other common somatic dysfunctions, such as intervertebral discitis, lumbar radiculopathy, primary sacral dysfunction, sacroiliitis, sciatica, and trochanteric bursitis.

(Image from http://www.concordortho.com/patient-education/topic-detail-popup.aspx?topicID=4214fc65d020761633286131e407d037)

Anatomical Considerations

The proper understanding of piriformis syndrome requires knowledge of the anatomy and anatomical variations in the relationships between the sciatic nerve and the piriformis muscle.

The piriformis muscle is flat, pyramid-shaped, and oblique. This muscle originates on the front of the sacrum and inserts at the greater trochanter of the femur. With the hip extended, the piriformis muscle is an external rotator of the hip; however, with the hip flexed, the muscle becomes a hip abductor.

In most of the population, the sciatic nerve exits the pelvis deep along the lower surface of the piriformis muscle. However, many developmental variations of the relationship between the sciatic nerve in the pelvis and piriformis muscle have been observed. In as much as 22% of the population, the sciatic nerve pierces the piriformis muscle, splits the piriformis muscle, or both, predisposing these individuals to irritation of the sciatic nerve.

From http://www.anatomyatlases.org/AnatomicVariants/NervousSystem/Images/70.shtml

Causes of Piriformis Syndrome

Piriformis syndrome can be caused by a variety of issues. The underlying mechanism is from irritation to the sciatic nerve. Below are some causes of irritation to the sciatic nerve as it passes the piriformis muscle:

1. Muscular problems

- Spasms and adhesions in the piriformis muscle cause compression and irritation of the sciatic nerve. Muscular damage or tightness can develop from a single injury or repetitive use injury. Vigorous physical activity can lead to such an injury- (commonly seen in athletes such as runners, cyclists, and dancers).

2. Postural

- Hyperlordosis (increased curvature of the low back) and increased foot pronation are both risk factors for piriformis syndrome

3. Traumatic

- Direct compression of the piriformis and/or sciatic nerve from an external soure such as a wallet.

4. Partial or total nerve anatomical abnormalities

- An anomaly in the nerve itself as it passes through the piriformis muscle can lead to dysfunction

5. Other causes can include the following:

- Pseudoaneurysms of the inferior gluteal artery adjacent to the piriformis syndrome

- Bilateral piriformis syndrome due to prolonged sitting during an extended neurosurgical procedure

- Cerebral Palsy

- Total hip arthroplasty

- Myositis ossificans

Stay tuned…… the next post will talk about how this problem is diagnosed and treated.

POSTERIOR IMPINGEMENT IN DANCERS

/in Sports Injury/by Dr. Kevin RosePosterior ankle impingement is a common cause of pain in ballet dancers. Other names for this condition are “os trigonum syndrome” and “nutcracker syndrome”. It is called “nutcracker syndrome” not because of its common occurrence in ballet at Christmas-time but because of the way the tissue of the ankle is squeezed at the ankle. The following is a brief overview of this condition and how it relates to dancers.

Posterior impingement of the ankle is often attributable to the presence of an accessory bone growth called an os trigonum or a Stieda process that is located just behind the talus (see x-ray for anatomy). The stress from repetitive plantarflexion by dancers, especially at a young age, is the suspected cause of the development of the os trigonum. Pain in posterior impingement occurs when the soft tissue of the ankle is pinched between the posterior lip of the tibia and the calcaneus. This occurs when the foot is in extreme plantarflexion such as during releve in the demipointe or en pointe positions.

Diagnosis

Proper diagnosis of posterior impingement is imperative for recovery from this injury. Posterior impingement attributable to an os trigonum is usually misdiagnosed as Achilles’ tendonitis/tendonopathy, peroneal tendonitis or flexor hallucis longus strain.

The two main symptoms of posterior impingement are a decrease in plantarflexion compared with the unaffected ankle and pain in the posterior region of the ankle. Often dancers are aware of a lack of ability to fully pointe in one foot compared to the other, this may be an early sign of impingement. Another common description dancer’s use is it feels like pinching in the heel during releve. Diagnosis is often aided by x-Rays of the ankle. It is best to request an x-ray to be taken during releve to evaluate the biomechanics of the injury. If there has been persistent pain for a period of 1– 4 months, local swelling, and radiographic assessment indicating a posterior ankle impingement, then an MRI should be performed.

Treatment for Posterior Impingement of the Ankle

Once posterior impingement is diagnosed focused treatment should begin. Non-surgical care is usually successful and should be the first line treatment. Treatment should be focused on taking pressure off of the tissue being pinched. Exercises should focus on engaging the deep muscles of the leg especially the deep flexors. One exercise that is helpful and can be done at home is a self traction maneuver with plantarflexion (see picture). The patient holds his or her ankle, as shown, with downward pressure and performs the motion with a bent knee. Bending the knee helps disengage the gastrocnemius muscle and soleus forcing the deep flexors to engage.  Another great exercise is ankle range of motion with traction applied by a therapist using very strong elastic bands. Dancers may experience relief with traction and feel they are able to fully plantarflex; this can also be a good way to support the diagnosis as Achilles’ tendonitis is often unchanged with traction. Manipulation of the ankle especially the talus can provide relief as well. Conservative therapy is successful in the majority of cases. Recovery may take several months.

Another great exercise is ankle range of motion with traction applied by a therapist using very strong elastic bands. Dancers may experience relief with traction and feel they are able to fully plantarflex; this can also be a good way to support the diagnosis as Achilles’ tendonitis is often unchanged with traction. Manipulation of the ankle especially the talus can provide relief as well. Conservative therapy is successful in the majority of cases. Recovery may take several months.

A surgical approach should only be adopted in the following cases:

- recurrent or unremitting symptoms in professional ballet dancers;

- persistent decreased plantarflexion compared with the unaffected ankle;

- failure of physical and medical therapies after 1– 4 months (depending on the level of the athlete/dancer);

- posterior impingement clinically suspected and indicated by both x-ray and MRI.

Ankle pain and heel pain is a common symptom in dancers and posterior impingement is only one of the causes. If you think you may be suffering from posterior impingement seek advice from a qualified healthcare professional with expertise in dance injury.

-Dr. Rose, DC, CCSP®

Dr. Rose is a Certified Chiropractic Sports Practitioner® with experience in dance medicine. He is currently Director of Physical Rehabilitation at Ballet San Jose and a member of the International Association of Dance Medicine and Science.

REFERENCES

Albisetti W, Ometti M, Pascale V, De Bartolomeo O: Clinical evaluation and treatment of posterior impingement in dancers. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2009;88:349–354.

Niek van Dijk C: Anterior and posterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Clin 2006;11:663– 83

F Cilli, M Akcaoglu: The incidence of accessory bones of the foot and their clinical significance. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2005;39:243– 6

POSTURAL STABILITY IN DANCERS AFTER INJURY

/in Sports Injury/by Dr. Kevin Rose Ballet dancers are widely known for their superior body control in various challenging body positions. In fact it has been found in recent studies that ballet dancers have better postural control when compared to other elite athletes. However, what has not been examined is the effect of injury on postural balance in dancers. A recent study in The American Journal of Sports Medicine by Lin, et al, addresses this vary issue.

Ballet dancers are widely known for their superior body control in various challenging body positions. In fact it has been found in recent studies that ballet dancers have better postural control when compared to other elite athletes. However, what has not been examined is the effect of injury on postural balance in dancers. A recent study in The American Journal of Sports Medicine by Lin, et al, addresses this vary issue.

Postural balance requires a combination of several different sensory inputs: visual, vestibular (inner ear), and somatosensory (from the skin, joints, muscles, etc). Somatosensory input gives the brain information about where the body is in space; this is called proprioception. These sensors can be damaged with ligamentous and muscular injuries such as ankle sprains and in turn lead to a deficit in proprioception. Proprioceptive deficits can put a dancer at more risk for re-injury or new injury.

The recent study by Lin was the first study that evaluated stability in dancers in ballet specific postures following an injury. Three different groups were studied: healthy dancers, injured dancers (with sprained ankles), and health non-dancers. Postural stability was evaluated on a balance sensor that monitors subtle deviations in stability. This was done with the eyes open and then again with the eyes closed to further stress the proprioceptive component of balance. As expected the injured dancers had decreased control not only in ballet specific positions but also in a simple single leg standing position when compared to healthy dancers. Surprisingly the injured dancers had worse stability control than the non-dancers. Many dancers, and other athletes, that I have treated often assume that a skill such as balancing will come back without training, however this is not the case, and as the study indicated it regresses to the point that is worse than untrained people.

The postural deficits were most notable in side to side control with single leg standing and front to back control with first and fifth position. Compensation was noted at the knee and hip joints in an attempt to make up for the injured ankle. The en pointe position crated the most stability issues; injured dancers were inferior in all directions of stability. With lateral ankle sprains the most commonly damaged ligament is the anterior talofibular ligament. This ligament is stressed maximally when the ankle is plantar flexed, such as during en pointe positions. It is not surprising that when this ligament is damaged the proprioception during pointe is significantly disturbed.

This study brings to light the importance of a thorough rehabilitation program that includes proprioceptive training in ballet specific positions. Typically a sprained ankle takes 6-8 weeks to recover. During this time it is critical to begin proprioceptive training to ensure that the balance deficits do not lead to further injury. Additionally if a dancer has a past injury of ankle sprain without proper rehabilitation it is likely that postural stability still remains and there is an increased risk to further injury. If this is the case, dancers should begin a 3-4 week proprioceptive training plan that includes ballet specific posture.

Dance injuries and rehabilitation are unique and should be managed by a healthcare practitioner that is experienced with the subtleties of dance medicine. Proprioception training for ballet typically includes balance exercises on an unstable surface such as a Bosu ball or stability disc. These exercises should be done in normal stance position as well as ballet specific positions. Whole body vibration may additionally add value as a proprioceptive trainer especially early during rehab when range of motion is limited. KinesioTape or RockTape are also good taping methods that help protect the joint and provide increased proprioception when applied properly. Keep in mind that a training plan should be designed specifically for each injury and you should not attempt to manage the injury without the supervision of an experienced healthcare practitioner.

BACKPACK SAFETY

/in Back Pain Prevention/by Dr. Kevin RoseBackpacks are a practical way for students to carry schoolbooks and supplies. They are designed to distribute the weight of its contents among some of the body’s strongest muscles; however, in recent years, the weight of student backpacks has increased dramatically and has become a public health concern. Studies show that heavy backpacks can lead to both back pain and poor posture, notes the American Chiropractic Association (ACA). In fact, in 2001 backpacks were the cause of 7,000 emergency room visits and countless complaints of muscle spasms, neck and shoulder pain.

Here are some tips on purchasing a backpack, packing a backpack, and wearing a backpack to reduce the risk of injury.

Purchasing a backpack, what does a good backpack need

- Wide( > 2), Padded Straps

The bag should have wide padded shoulder straps. Wide straps and padding distribute the load over more area of

the shoulder and alleviate pressure points. - Padded Back

The back of the backpack should padded as well to encourage the pack to sit flat against the back. - Lightweight

Reducing the overall weight carried begins with a light backpack. The stress on the back is caused by the weight of the bag, don’t forget that the weight of the bag contributes to the overall weight. Anything you can do to reduce that weight will reduce the stress. - Waist Strap

A waist strap dramatically helps direct the load away from the shoulders and onto the much stronger waist and hip muscle group. - Proper Size

Use the chart below for general recommendations by age or for more accuracy you can take measurements of your child’s back. The width should be from the outside ridge of the one shoulder blade to the other. The height should be from the shoulders to the waist line (belly button) plus two inches. See the diagram below to help with measuring.

Loading a Backpack

- Load heavy items close to the back (the back of the pack)

Heavy flat items should be placed against the back. This increases the body’s ability to support the weight with stronger muscle groups such as the hips and core. - Don’t overload (see weight chart below)

As a general rule the weight of the backpack should not be more than 15-20% of the students body weight. It should not exceed 25 pounds in any case. Below is a table with the recommended weight to be carried based on the student’s weight.

How to wear a backpack properly

- Wear BOTH straps

This helps distribute the load more evenly and helps hold the load more securely to the back. Wearing one strap can lead to shoulder and back pain. - Adjust shoulder straps so the backpack fits snugly against the back

The back pack should rest no lower than 4 inches below the waist line. Remember that the waistline is in line with the belly button not the top of pelvis. - Fasten waist belt and adjust strap length to secure and distribute the weight evenly

The benefits of the waist strap can only be seen if the strap is worn. Don’t forget to have your student fasten it when wearing. - The lower bulk of the backpack should rest in the curve of the lower back and not more than four inches below the waist

This also contributes to allowing the stronger muscles of the hips and shoulders to support the load.

Other considerations

- Monitor what your child is carrying to school each day to help him or her avoid carrying unnecessary items which add weight to the backpack.

- Periodically check to see if your child is wearing his or her backpack correctly.

- Assist your child with cleaning out and organizing the backpack weekly.

- If the backpack weighs more than 15% of your child’s body weight have child carry a heavy book or two under his or her arm.

- Ask your child if he/she has any discomfort during or after wearing the backpack.

- Help your child file work at home so he/she only needs to bring required work to school each day.

- Talk to your child and teachers about ways to reduce backpack weight.

- Some books can be found online at low cost. Consider purchasing a second copy to keep at home so your child doesn’t have to carry it back and forth.

- Share any concerns about backpack weight with your child’s teacher or administrator.

Taking the time to make careful consideration regarding your child’s backpack use is important to prevent injury. If your child does develop back pain have him or her seen by a qualified health professional for proper diagnosis and treatment.

-Dr. Rose, DC

Dr. Rose is a San Diego Chiropractor located in Mission Valley. More information regarding the services he provides can be found at www.RoseChiropracticSD.com.

References

American Chiropractic Association. Backpack Misuse Leads to Chronic Back Pain, Doctors of Chiropractic Say. Accessed at acatoday.org

Admas, Chris. A Fitting Guide for a Child’s Backpack. 2006.

Howard County Public School System. Backpack Safety Guidelines

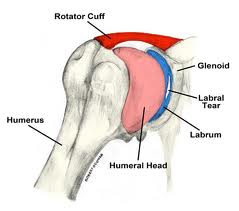

Labral tears of the shoulder: surgery or not?

/in Sports Injury/by Dr. Kevin Rose

At the recent American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, a comparison of non-surgical treatment and surgical treatment for SLAP labral tears of the shoulder in baseball players was presented. The labrum is a cartilage structure that makes the  socket of the shoulder deeper and helps hold the upper arm. SLAP tears are a specific type of labral injury that is mainly caused by repetitive throwing. Although surgical repair of SLAP tears is common, little is known about the effectiveness of nonsurgical pain relief and the effects of surgery on performance.

socket of the shoulder deeper and helps hold the upper arm. SLAP tears are a specific type of labral injury that is mainly caused by repetitive throwing. Although surgical repair of SLAP tears is common, little is known about the effectiveness of nonsurgical pain relief and the effects of surgery on performance.

|

Return to play |

Return to same level of play |

|

|

Surgery |

48% |

7% |

|

Non-Surgery |

40% |

22% |

The return to play rate in SLAP injuries is low, typically reported at less than 50%. In this study the return to play rate for those that underwent surgery was 48% while those that underwent rehabilitation was only slightly lower at 40%. The most interesting finding in this study however was that the group that had surgery rarely, only 7% of the time, returned to the level of play that they had previously attained. The non-surgery group in comparison returned to the same level of play 22% of the time.

John E. Kuhn, MD, associate professor of orthopedic surgery and rehabilitation and chief of shoulder surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee described the findings as “very significant” and summed up the findings:

“A lot of these throwing athletes can be treated non-operatively,” Dr. Kuhn said. “They had very good success with rehabilitation. That suggests that patients can throw with SLAP tears, and that not every SLAP tear needs to be repaired,” he said. “Many can be rehabilitated; the sources of pain or disability may not even be the SLAP lesion itself,” he added. The research suggests that surgery in this patient population really should be a career-salvaging option, he explained. “It really shouldn’t be something you throw at somebody quickly or early. Rehab them, do everything you can to prevent surgery,” he concluded.

Another take home message from these findings that should be discussed further is the importance of avoiding shoulder injuries from throwing. As stated the percentage of those injured with SLAP tears that return to play is less than 50%. The best advice then logically is to avoid getting a SLAP tear altogether. Unfortunately, there is no sure fire way to avoid getting a tear if you are a pitcher. However what can be done is limiting the risk factors for injury. Risk factors for throwing injuries include a decrease in shoulder internal rotation, poor scapular control, and high pitching load. These risk factors should be screened for and proper preventative exercises should be built into any strength and conditioning program for baseball players, especially pitchers. Non surgical treatment in these cases included rehabilitation that focused on stretching the posterior capsule of the shoulder to increase internal rotation and training the scapular muscles to hold the scapula in a stable position during the wind-up and cocking phase of the throwing motion. These exercises should also be at the core of any preventative arm care program for baseball players. Manual therapy, including myofascial release and Graston treatment can also be beneficial to aid in increasing range of motion. These preventative strategies should be overseen by a healthcare provider knowledgeable in baseball injuries.

If you would like more information about how to recover from or prevent shoulder injuries contact our office today.

Another article outlining preventative exercises is coming soon…

-Dr. Kevin Rose, DC

References

Yin, S.”SLAP Tears Often Treated Successfully without Surgery”. Medscape Medical News, July 7 2012.

Wilk et al. Passive range of motion characteristics in the overhead baseball pitcher and their implications for rehabilitation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012 Jun;470(6):1586-94.

Wilk et al. Shoulder injuries in te overhead athlete. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009 Feb;39(2):38-54.

Kinesiology Tape for Dancers

/in Sports Injury/by Dr. Kevin RoseMany dance medicine specialists and dancers have begun to use Kinesiotape as a staple to manage their injuries. Developed  more than 25 years ago in Japan by chiropractor Dr. Kenzo Kase, the Kinesiotape method drew worldwide interest when the U.S. Olympic volleyball player Kerri Walsh wore the tape to support her shoulder during the 2008 Games in Beijing. Now many elite athletes, including dancers use Kinesiotape. Unlike traditional athletic tape, the latex-free Kinesio stretches easily, and permits greater range of motion, making it popular with dancers. It allows the dancer to perform while still protecting them from further injury. “The old way of taping was stiff and tried to support ligaments, but we have learned it gave less support than we suspected,” says Dr. Rebecca Clearman, M.D, “Kinesiotape, on the other hand, helps dancers self-correct. (For instance) if a dancer is hyper-extending, it can serve as a reminder at the end of the range to not go as far.”

more than 25 years ago in Japan by chiropractor Dr. Kenzo Kase, the Kinesiotape method drew worldwide interest when the U.S. Olympic volleyball player Kerri Walsh wore the tape to support her shoulder during the 2008 Games in Beijing. Now many elite athletes, including dancers use Kinesiotape. Unlike traditional athletic tape, the latex-free Kinesio stretches easily, and permits greater range of motion, making it popular with dancers. It allows the dancer to perform while still protecting them from further injury. “The old way of taping was stiff and tried to support ligaments, but we have learned it gave less support than we suspected,” says Dr. Rebecca Clearman, M.D, “Kinesiotape, on the other hand, helps dancers self-correct. (For instance) if a dancer is hyper-extending, it can serve as a reminder at the end of the range to not go as far.”

Kinesiotape can be used to stimulate or relax a muscle, depending on the direction of the recoil of the stretched tap. Whether relaxing or activating, the tape gets placed along the line of the muscle. For activating, the direction of the tape goes from muscle origin to insertion. The tape’s degree of stretch determines the strength of the recoil action, so each application can be tailored to a dancer’s needs.

It’s like a brace, but better, because of it allows greater range of motion and also provides proprioceptive input (joint balance). Kinesiotape comes in a variety of brands and can be purchased by the consumer, however initially the tape should be applied by a dance medicine professional with knowledge of dance mechanics. After several sessions the injured dancer can learn to put the tape on properly by himself/herself.

Kinesiotape is not a magic bullet. Proper diagnosis of the injury by a qualified healthcare professional is always the first step and during recovery, proper rehabilitation and correction of biomechanical errors are keys.

-Dr. Rose is a San Diego Chiropractor and a Certified Chiropractic Sports Practitioner®. He is a member of the International Association of Dance Medicine and Sciences and has experience with ballet dancers from youth to professional.

Preventing Dance Injuries

/in Sports Injury/by Dr. Kevin RoseThe  physical demands placed on the bodies of dancers have been shown to make them just as susceptible to injury as football players. For this reason, more emphasis should be placed on creating awareness of risk and preventing injuries in dancers. Most dancers begin dancing at a young age, the repetitive practice of movements that require extreme flexibility, strength, and endurance make them prime candidates for overuse injuries. In fact, there is little doubt that the vast majority of injuries are the result of overuse rather than trauma. These injuries tend to occur at the foot, ankle, lower leg, low back, and hip. These injuries show up with greater frequency in dancers as they age, so it is extremely important to emphasize what the young dancer can do to prevent future injuries.

physical demands placed on the bodies of dancers have been shown to make them just as susceptible to injury as football players. For this reason, more emphasis should be placed on creating awareness of risk and preventing injuries in dancers. Most dancers begin dancing at a young age, the repetitive practice of movements that require extreme flexibility, strength, and endurance make them prime candidates for overuse injuries. In fact, there is little doubt that the vast majority of injuries are the result of overuse rather than trauma. These injuries tend to occur at the foot, ankle, lower leg, low back, and hip. These injuries show up with greater frequency in dancers as they age, so it is extremely important to emphasize what the young dancer can do to prevent future injuries.

WHAT CAUSES DANCE INJURIES?

Dancers are exposed to a wide range of risk factors for injury. The most common issues that cause dance injuries include:

- Type of dance and frequency of classes, rehearsals, and performances

- Duration of training

- Environmental conditions such as hard floors and cold studio

- Equipment used, especially shoes

- Individual dancer’s body alignment

- Prior history of injury

- Nutritional deficiencies

How to Prevent Dance Injuries

Getting and keeping dancers free of injury in a fun environment is key to helping them enjoy a lifetime of physical activity and dance. With a few simple steps, and some teamwork among parents, teachers and health professionals, dancers can keep on their toes and in the studio with a healthy body.

Key Points

Dancers should remember a few key things to prevent injury:

- Wear properly fitting clothing and shoes

- Drink plenty of fluids

- Resist the temptation to dance through pain

- Pay close attention to correct technique

- Be mindful of the limits of your body and do not push too fast too soon

- Perform proper warm-up and cool-down

Parental Oversight

Parents play a large role in injury prevention. First, they must be careful not to encourage their children to advance to higher levels of training at an unsafe rate. Specific to ballet, parents should ensure that the decision to begin pointe training is not made before the child’s feet and ankles develop enough strength. Age 12 is the generally accepted lower limit, but strength and maturity are more important than age.

Proper Instruction

The first line-of-defense to prevent injuries may be dance instructors. From the onset of instruction teachers should establish a class environment where students are not afraid to share that they are injured and need a break. Students should also be consistently instructed on the importance of warm-ups and cool-downs, proper equipment, and at what point, whether by age or maturity, it is appropriate to move on to the next level of dance.

Health Care and Screening

Health professionals play a significant role not only in treating and rehabilitating the injuries dancers incur, but also in preventing them. Dancers respond well to providers who respect both the aesthetics and intensity of dance. Experienced providers can initiate and facilitate screening sessions for dancers to help identify potential problems and prevent future injuries. They should be considered a natural part of a dancer’s career and sources of insight into staying healthy. A dancer should return after an injury only when clearance is granted by a health care professional.

REFERENCES

Clippinger, K. Dance Anatomy and Kinesiology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2007.

Howse, J. Dance Technique and Injury Prevention. 3rd ed. London: A & C Black, 2000.

Solomon, R, J. Solomon, and SC Minton. Preventing Dance Injuries. 2nd ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2005.

www.stopsportinjuries.org

Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation

/in Uncategorized/by Dr. Kevin RoseAt Proform Sports Chiropractic, we help create lifelong musculoskeletal health, emphasizing physical activity and exercise throughout life. Our goal is to prevent injury and achieve optimal health, mobility, and quality of life throughout each person’s lifespan.

Our two primary areas of interest are musculoskeletal injury prevention and rehabilitation. Our offfice focuses on on injury prevention and on effective treatment and rehabilitation that are essential to putting the person back on the path to optimal health.

PEAK FORM NEWSLETTER SIGN UP

Our Office